BASEL, AD 20–1815

Archaeology at

St. Alban-Graben

From 2018 to 2021, construction of the Kunstmuseum carpark was monitored by the Archaeological Service of Canton Basel Stadt. The finds from the archaeological investigations provided a fascinating insight into the history of Basel.

This is where we excavated

St. Alban-GrabenCH-4051 Basel

The name of the street, “St. Alban-Graben” ( in English St. Alban’s Ditch ), reminds us that this was where the defensive ditch of the early 13th century inner city wall was once located. Construction of a new carpark at the Kunstmuseum required deep intrusions into the ground, both at the site of the former city moat and in an area directly adjacent to it, which had been developed since the Roman period.

Although a massive trench was cut into the Roman-period features when the inner city wall and its moat were built in the Middle Ages, archaeologists were able to record the final remnants of the Roman settlement, which had existed from the 1st century onwards in front of where the Kunstmuseum stands today. What came as quite a surprise was the discovery of two dry-wall Roman shafts beneath the medieval city moat at a depth of 7 m (23 feet). Originally used as wells, the shafts were later filled with partial skeletons of horses and dogs and even human remains.

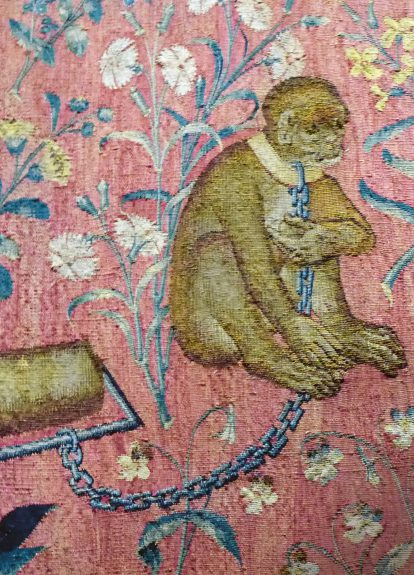

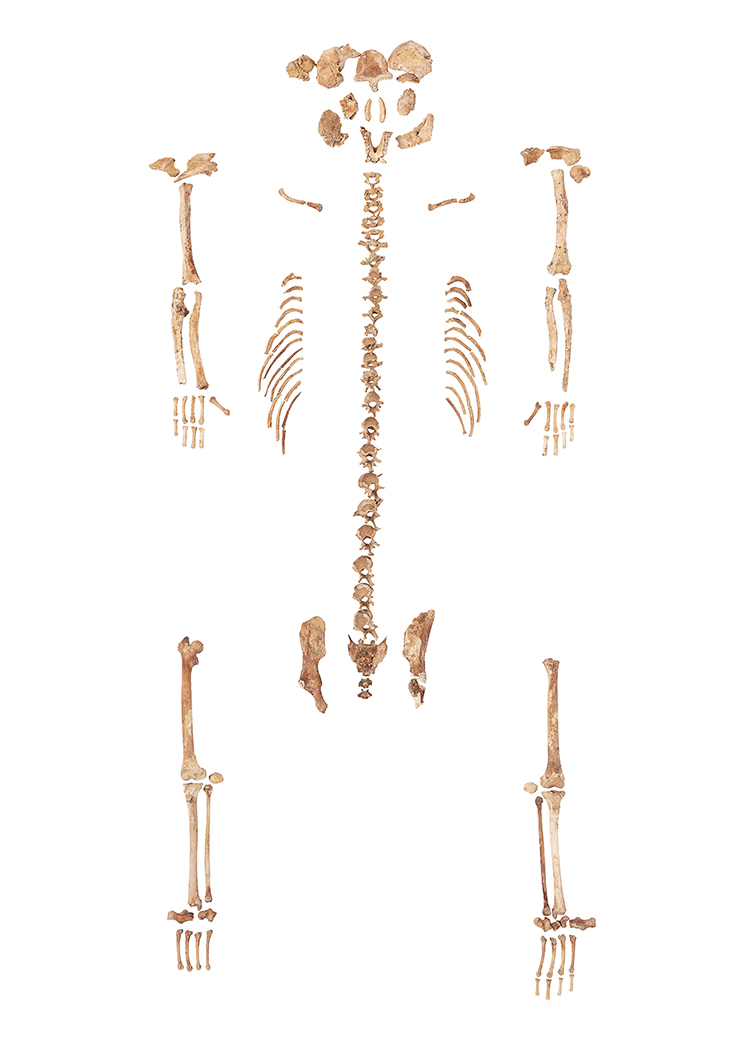

Remnants of the medieval city wall, or so-called inner city wall, were uncovered in various locations during the construction project beneath the footpath and the façades of the present-day houses on the side of the street facing Münsterhügel hill. The skeleton of a Barbary macaque, which came to light in a latrine tower built onto the city wall, was a sensational find. The animal had been kept as a pet in the Middle Ages. Healed bone fractures and traces of inflammation suggest that it was rather ill-treated.

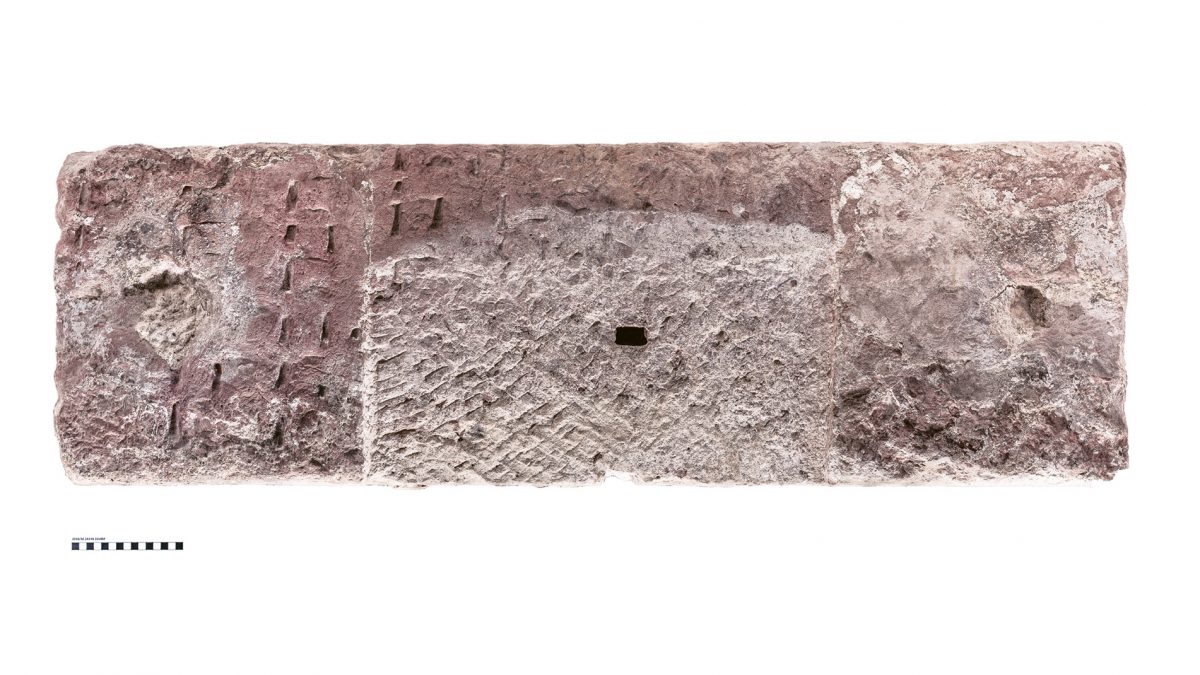

Several fragments of tombstones found during the excavation came from the cemetery of Basel’s first Jewish community, which was located at Petersplatz square. The persecution of Jews following an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1348/49 led to the community being crushed and driven out of the city; the cemetery was destroyed, and the tombstones reused as covering slabs for the countermure (the retaining wall of the city moat). When the moat was abandoned, the tombstones were removed and reused a second time to build drainage shafts at St. Alban-Graben in 1815. This was where they were discovered by the archaeologists.

Find out more about the results of the excavation (in German only).

Read moreFind out more about excavations of the Archaeological Service of Basel Stadt (in German only).

Read moreThe free audio guide app by the Archaeological Service of Basel Stadt shows you around four original sites from the Celtic, Roman and medieval periods of Basel’s history, where archaeological information points have been set up.

Read moreNewsletter

Sign up to our newsletter. Stay informed about current excavations, special finds and guided tours.